#2 prairial an III

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Thermidorian Reaction

The Thermidorian Reaction refers to the period of the French Revolution (1789-1799) between the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 27-28 July 1794 and the establishment of the French Directory on 2 November 1795. The Thermidorians abandoned radical Jacobin policies in favor of conservative ones, seeking the restoration of a stable constitutional government and economic liberalism.

The Thermidorians came to power by conspiring against and overthrowing Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794). After his execution, the Thermidorian regime set about dismantling the Reign of Terror by purging the Jacobins from positions of power and by violently suppressing their ideology in the First White Terror. Their efforts to return stability to France resulted in pursuance of conservative policies reminiscent of earlier phases of the Revolution; they restored freedom of religion, reintroduced free market capitalism, and allowed the return of some aristocratic émigrés into France, leading to a rise in openly royalist sentiment. These policies were met with mixed success.

The new regime was generally unpopular with the French people, who faced increased rates of poverty and starvation during the 15 months of Thermidorian rule. This led to multiple attempted coups, the most significant of which was the Uprising of 1 Prairial Year III (20 May 1795), in which insurgents demanded bread and the adoption of the dormant constitution of 1793, which had been written by the Jacobins. After the uprising had petered out, the Thermidorians wrote their own constitution of Year III (1795), which established the French National Directory.

Thermidorians

The name 'Thermidorians', ascribed to the conspirators against the Robespierrist regime, is derived from the mid-summer month of Thermidor in the French Republican calendar, during which the coup took place. Though possessing a shared distaste for Robespierre, the Thermidorians had little else in common. Some of them had been willing and enthusiastic participants of the Terror before they had run afoul of Robespierre and needed to be rid of him to save their own skins. Others had detested the Terror from the start and had been eager to bring it down. Many were conservative republicans who represented the centrist mass of Convention deputies known as the 'Plain', who desired to turn back the clock to the way the Revolution had been in 1792, pre-Terror; others wished to go back further, seeking a second attempt at constitutional monarchy, as in 1791.

This lack of consensus, as well as the absence of dominating personalities to rally behind, contributed to the ineffectiveness and unpopularity of the Thermidorian Convention. The lackluster success of their policies has certainly marred the Thermidorians' legacy. Their detractors viewed them as an unremarkable interlude between Robespierre and Napoleon at best; at worst, they were the gravediggers of their own Revolution, one-time revolutionaries seduced and corrupted by the heights of power. This latter context was used by Leon Trotsky in his 1937 book The Revolution Betrayed, in which he refers to the rise of Joseph Stalin as a Soviet Thermidor.

While there may be elements of truth to these claims, historian Bronisław Baczko asserts that the Thermidorians were merely being realistic. The Revolution, having lost much of its momentum, grew closer to succumbing to fatigue with every month. It was becoming clearer that the Revolution could no longer live up to the promises made in 1789. Therefore, rather than willfully burying the Revolution, Baczko argues that the Thermidorians realized these limitations and simply did their best to work around them. After the violence of the Terror, many French people desired stability over revolutionary progress, which the Thermidorians attempted to give them. In either case, the period of the Thermidorian Reaction marked a counter-revolution of sorts, moving away from the radical progress of the Jacobins and back toward stable conservatism.

Continue reading...

23 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Le Comité de sureté générale arrête que le député Prieur de la marne Sera en éx.on [exécution] du Decret d’hier arrêté à L’instant & Conduit au Comité de sureté G.le [générale] & les Scellés apposés Sur Ses papiers Charge de L’ex.on [l'exécution] du present La Comm.on [Commission] de Police administrative Les Rep.ts [représentants] &ca signé Mathieu [Matthieu], Pemartin [Pémartin], Pierre Guyomar[,] Cales [Calès], Courtois, auguis & Delecloy./

Arrêté du CSG du 2 prairial an III (AN F7 4774 83, dossier Prieur de la Marne, député).

#il y a 225 ans#2 prairial an III#Révolution française#Réaction thermidorienne#Prieur de la Marne#an III#Prairial#Comité de Sûreté générale#Matthieu#Pémartin#Guyomar#Calès#Courtois#Auguis#Delecloy

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If today, no specialist can make the Revolution end with the death of Robespierre – as Michelet did –, there is no doubt that a political rupture occurred in the months that followed. The so-called period of the Thermidorian Convention, which stretches from 11 Thermidor Year II (29 July 1794) to the establishment of the Directory on 4 Brumaire Year IV (26 October 1795), saw the emergence of a discourse that legitimised the rejection of the Constitution that had been adopted on 24 June 1793 (and ratified by the primary assemblies on 9 August), and more generally of the democratic Republic of Year II that one associated with the “Terror” and with the “tyranny” of “the deliberative anarchy”, to use the Thermidorian vocabulary.

The purification of the Convention of most of the Montagnards, combined with the return, at the start of Year III, of the deputies that had been excluded in the aftermath of the Revolution of 31 May / 2 June 1793, brought about a brutal swing to the right of the Assembly. The (sometimes physical) elimination of the political personnel of Year II on account of “terrorism” of “Robespierrism”, the liquidation of a great part of the democratic and social legislation that had been adopted in Year II, the progressive dismantlement of the institutions d’exception of the revolutionary government provoked a political “reaction”, facilitating the apparition of the “White Terror” which struck the republican personnel in most of the departments.

The repression of the Parisian popular riots of Germinal and Prairial Year III, demanding “bread and the Constitution of 1793″, facilitated the process which resulted in the introduction of a new Constitution, which was adopted on 5 Fructidor Year IV (22 August 1795), re-founding the republic on a confiscation of the exercise of sovereignty by the “honnêtes gens”, i.e. by the owners, as the deputy Boissy d’Anglas affirmed on 5 Messidor Year III (23 June 1795).

Le Directoire. La république sans la démocratie (Marc Belissa / Yannick Bosc), p. 14f.

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The revolutionary journées (G.-R. Ikni)

The expression, beyond its apparent simplicity, in fact poses a delicate problem concerning its definition. Does it have to be understood in the sense which gives actors and contemporaries to it, or in the sense used by the historians? Among the first, three tendencies took shape: it was understood either as a matter, as Prudhomme does in his Révolutions de Paris, of celebrating the memorable journées of the Revolution in the form of engravings, or, in the militant, « activist » sense, as a matter for the sans-culottes of preparing a new insurrection. Thus, in March 1793, and more still in late May, the people of Paris made reference to the two precedent « levées en masse » of 14 July 1789 and 10 August 1792. It was a question of exercising, in its spirit, the right to insurrection in the name of the entire people. Such a journée rests on a preparation by a committee (the insurrectional commune on 10 August, the Central Committee of the Sections on 31 May 1793) which, in principle, dissolves once victory is achieved. But beyond that, the Assemblies, based on its popular insurrections or on their own decisions (the proclamation of the Republic, the condemnation of the king), organised an adress and commemorative practices: the stamping of medaillons, the erection of monuments, the payment of pensions to the victims and, finally, festivals (18 Floréal Year II) which expressed the speech of the Revolution on itself (M. Ozouf) by emphasising the restored time of foundation. Hence, there was, from this point of view, an evident link between the revolutionary and the memorable journée, since it is understood that Parisian space is the theatre par excellence of this alchemy of the new times. Let us finally highlight the contribution of administrative historiography to the development of the calendar of the journées, compiled in the index of Rondonneau's collection of laws. Whatever view one holds, this calendar cuts out, organises and, finally, perpetuates certain « sites of memory » in accordance with a representation, i.e. an ideological reconstruction of the events, either as a call to « make history » by reiterating a founding success, or as the organisation, based on a sequence of « dates », of a collective memory that is immediately operational, at once allowing to determine who is who, a patriot or a suspect, depending on their attitude in the « critical » moments of the Revolution, or, at last, while the confrontation moves away, as a mere means of obscuring the role of some, in order to better celebrate the procession of the victors of history. The effects of this selection are obviously very diverse, both in the outline of the number of reserved journées and in their nature. In the work of Rondonneau, it amounts to a veritable inflation, with twenty-two journées in total, where gatherings, insurrections, coups d'état and « national » festivals intermingle, each being selected from the perspective of the power that is in place. C. Desmoulins, in the first issue of his Vieux Cordelier, defined the veterans of the Revolution based on five « campaigns » (14 July, 5-6 October 1789, 17 July 1791, 10 August 1792, 31 May - 2 June 1793). The latter, which marks the expulsion of the Girondins from the Convention, was, as one can imagine, doomed to oblivion by the Thermidorian réacteurs who, on the other hand, celebrated 9 Thermidor Year II (the fall of the Robespierrists).

As to modern historians, they have generally adopted the equivalence journée = popular insurrection. Thus, G. Lefèbvre who, to the journées that were demanded by the sans-culottes, adds September 1792 (the prison massacres), 4-5 September 1793 and, for the following period, the popular insurrections of Germinal-Prairial Year III and the royalist uprising of 13 Vendémiaire Year IV. The popular definition was thereby expanded. The term journée in fact designates any revolutionary or counter-revolutionary insurrection. As for M. Reinhard, he noted perceptible differences between 14 July 1789, the « most Parisian of the journées », and 10 August, which was, in fact, national, and which, additionally, could not be reduced to a single journée. Let us also note in this regard that every Parisian revolutionary journée tended towards becoming national, to the extent that, by means of festivals, it was reiterated as a simulacrum in multiple local festivals.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image taken from page 11 of 'Les Guerres Civiles en France pendant la Révolution. La Révolte de Toulon en prairial an III'

Image taken from: Title: "Les Guerres Civiles en France pendant la Révolution. La Révolte de Toulon en prairial an III" Author: Masson, Frédéric Shelfmark: "British Library HMNTS 9220.cc.2." Page: 11 Place of Publishing: Paris Date of Publishing: 1875 Issuance: monographic Identifier: 002417571 Explore: Find this item in the British Library catalogue, 'Explore'. Download the PDF for this book (volume: 0) Image found on book scan 11 (NB not necessarily a page number) Download the OCR-derived text for this volume: (plain text) or (json) Click here to see all the illustrations in this book and click here to browse other illustrations published in books in the same year. Order a higher quality version from here. from BLPromptBot https://ift.tt/2SioW5m

0 notes

Photo

Thermidorian Reaction

The Thermidorian Reaction refers to the period of the French Revolution (1789-1799) between the fall of Maximilien Robespierre on 27-28 July 1794 and the establishment of the French Directory on 2 November 1795. The Thermidorians abandoned radical Jacobin policies in favor of conservative ones, seeking the restoration of a stable constitutional government and economic liberalism.

The Thermidorians came to power by conspiring against and overthrowing Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794). After his execution, the Thermidorian regime set about dismantling the Reign of Terror by purging the Jacobins from positions of power and by violently suppressing their ideology in the First White Terror. Their efforts to return stability to France resulted in pursuance of conservative policies reminiscent of earlier phases of the Revolution; they restored freedom of religion, reintroduced free market capitalism, and allowed the return of some aristocratic émigrés into France, leading to a rise in openly royalist sentiment. These policies were met with mixed success.

The new regime was generally unpopular with the French people, who faced increased rates of poverty and starvation during the 15 months of Thermidorian rule. This led to multiple attempted coups, the most significant of which was the Uprising of 1 Prairial Year III (20 May 1795), in which insurgents demanded bread and the adoption of the dormant constitution of 1793, which had been written by the Jacobins. After the uprising had petered out, the Thermidorians wrote their own constitution of Year III (1795), which established the French National Directory.

Thermidorians

The name 'Thermidorians', ascribed to the conspirators against the Robespierrist regime, is derived from the mid-summer month of Thermidor in the French Republican calendar, during which the coup took place. Though possessing a shared distaste for Robespierre, the Thermidorians had little else in common. Some of them had been willing and enthusiastic participants of the Terror before they had run afoul of Robespierre and needed to be rid of him to save their own skins. Others had detested the Terror from the start and had been eager to bring it down. Many were conservative republicans who represented the centrist mass of Convention deputies known as the 'Plain', who desired to turn back the clock to the way the Revolution had been in 1792, pre-Terror; others wished to go back further, seeking a second attempt at constitutional monarchy, as in 1791.

This lack of consensus, as well as the absence of dominating personalities to rally behind, contributed to the ineffectiveness and unpopularity of the Thermidorian Convention. The lackluster success of their policies has certainly marred the Thermidorians' legacy. Their detractors viewed them as an unremarkable interlude between Robespierre and Napoleon at best; at worst, they were the gravediggers of their own Revolution, one-time revolutionaries seduced and corrupted by the heights of power. This latter context was used by Leon Trotsky in his 1937 book The Revolution Betrayed, in which he refers to the rise of Joseph Stalin as a Soviet Thermidor.

While there may be elements of truth to these claims, historian Bronisław Baczko asserts that the Thermidorians were merely being realistic. The Revolution, having lost much of its momentum, grew closer to succumbing to fatigue with every month. It was becoming clearer that the Revolution could no longer live up to the promises made in 1789. Therefore, rather than willfully burying the Revolution, Baczko argues that the Thermidorians realized these limitations and simply did their best to work around them. After the violence of the Terror, many French people desired stability over revolutionary progress, which the Thermidorians attempted to give them. In either case, the period of the Thermidorian Reaction marked a counter-revolution of sorts, moving away from the radical progress of the Jacobins and back toward stable conservatism.

Continue reading...

19 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Séance de la Convention nationale du 2 prairial an III d'après le Moniteur universel (par laquelle on voit comment la version des faits donnée pour le Moniteur pour la séance de la veille a été reconstituée post hoc, Réimpression de l'ancien Moniteur, t. XXIV, n° 247, p. 518-523)

GOULY [colon esclavagiste, député de l'Isle-de-France (Île Maurice)] : On a dit tout à l’heure qu’on ne devait pas mettre hors la loi les hommes qui sont en prison ; ce principe est sacré : mais les hommes qui ont été arrêté hier soir étaient déjà hors la loi ; il suffit de constater l’identité des personnes, pour qu’on puisse les frapper. (Vifs applaudissements.) Le temps de l’indulgence est passé. (Nouveaux applaudissements.)

[...]

[On ne suit pas Gouly et] Le décret est rendu dans les termes suivants :

« La Convention nationale décrète d’accusation les représentants du peuple Duquesnoy, Duroy, Bourbote [Bourbotte], Prieur (de la Marne), Romme, Soubrany, Goujon, Albitte aîné, Peyssard, Lecarpentier (de la Manche), Pinet aîné, Borie et Fayau, décrétés d’arrestation dans la séance du 1er prairial ;

« Et les représentants Ruamps, Thuriot, Cambon, Maribon-Montaut, Duhem, Amar, Choudieu, Chasles, Foussedoire, Huguet, Léonard Bourdon, Granet, Levasseur (de la Sarthe), Lecointre (de Versailles), décrétés d’arrestation dans les séances des 12 et 16 germinal ;

« Et charge ses comités de sûreté générale et de législation de lui faire un rapport, dans trois jours, pour déterminer le tribunal et la commune dans lesquels ils seront jugés. (On applaudit.)

[...]

BOURDON [de l'Oise] : Vous venez de porter un décret d’accusation ; je dois acquitter ma conscience sur le compte d’un de ceux qui s’y trouvent compris sans de grands motifs. Ruhl [Rühl], ce vieillard de soixante-dix ans, hydropique, ne me paraît pas suffisamment accusé ; je n’ai entendu lui reprocher que quelques paroles adressées au peuple égaré. J’ai vécu longtemps avec ce vieillard, et j’ai appris à le respecter. Cependant je saurai faire céder à la justice les sentiments les plus doux : s’il est criminel je cesse de le défendre ; mais je désire être convaincu avant d’user de toute la rigueur des lois, et je demande qu’il reste en arrestation jusqu’à ce que les comités fassent un rapport.

BOISSY : Je demande à rendre compte d’un fait : Ruhl [Rühl] m’a apporté au bureau une motion écrite, tendant à décréter qu’il ne serait porté aucune atteinte à la constitution de 1793, et que la Convention s’occuperait sans relâche d’assurer les subsistances de Paris. Je lui représentai qu’il était impossible de délibérer, et je priai de ne point insister ; il se retira ; le papier fut enlevé par eux qui m’environnaient.

LEGENDRE : La proposition de Bourdon est sage ; je demande qu’on l’adopte.

« La Convention décrète que Ruhl [Rühl] restera en arrestation jusqu’à ce que le comité fasse un rapport à son égard.

*** : Je demande la même faveur pour Prieur (de la Marne) : j’ai été toujours près de lui, il n’a pas dit un seul mot.

[...]

Le membre qui avait déjà parlé en faveur de Prieur (de la Marne) reprend la parole ; il assure lui avoir entendu dire aux factieux : « Enfants, laissez la Convention libre, elle fera de bonne [sic] lois ; vous aurez du pain ; n’attaquez point l’intégralité [le Journal des débats et des décrets met "intégrité"] de la représentation nationale. »

BOURDON [de l'Oise] : Je suis obligé de dire que cette nuit, me promenant dans le salon de la Liberté avec mon collègue Quenet, et notre conversation roulant sur les malheureux événements dont nous avions été témoins, il me dit qu’au moment où le comité fit entrer les bons citoyens pour chasser les factieux de votre salle, il entendit Prieur crier deux fois : « A moi, à moi, braves sans-culottes, marchons ! »

QUENET [Quéinnec, ancien Brissotin et député du Finistère, où Prieur a été envoyé comme représentant en mission] : Je n’ai pas bien distingué si c’était Prieur, parce que ma vue est faible ; mais j’ai entendu le cri, et j’ai reconnu sa voix.

L’assemblée maintient le décret contre Prieur.

#il y a 225 ans#2 prairial an III#Révolution française#Réaction thermidorienne#Prieur de la Marne#an III#Prairial#derniers montagnards#martyrs de prairial#Rühl#Gouly#Bourdon de l'Oise#Boissy d'Anglas#Legendre#Quéinnec

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Du 2 prairial l’an trois de la République française une & indivisible. le comité de suretté [sic] generale arrette [sic] que le Representant du peuple Prieur de la marne, restera dans sa maison en etat d’arrestation, jusqu’a nouvel ordre, a la garde d’un gendarme, les membres composant le comité de suretté [sic] generale [sceau du CSG] [Signés :] Pemartin pierre Guyomar Monmayou Bergoeing

Archives nationales, F7 4774 83. Arrêté du Comité de sûreté générale du 2 prairial an III concernant l’arrestation de Prieur de la Marne, décrété d’arrestation le 1er, suite à son implication dans l’insurrection (que l’on a pourtant de bonnes raisons de croire exagérée : l’insurrection servait plutôt de prétexte à un règlement des comptes contre les derniers montagnards).

Prieur sera décrété également d’accusation le 2, mais je ne suis pas sûre s’il y a un moyen de savoir si c’était avant ou après cet arrêté. Le CSG a aussi cet autre arrêté (daté par mégarde du 1er) :

Du 1.er [sic] Prairial, an 3.e &.

Le comité de sureté Générale arrête qu’il sera donné un Gendarme de plus pour la garde du c.en Prieur de la Marne, mis en état d’arrestation par Décret d’hier,

Les membres du comité de sureté Générale

signé Monmayou, Pierre Guyomar, Pemartin,

P. C. Conforme

== Jollivet

Reçu l’original Lambert Brigr

#il y a 222 ans#Prieur de la Marne#Comité de sûreté général#2 prairial an III#prairial an III#Réaction thermidorienne#Révolution française#an III

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know about reliable estimates of the death toll of the first white terror during the thermidorian reaction?

The key word here is of course “reliable”, which is much trickier for the massacres of the Thermidorian Reaction, since they tended to be extra-legal. But not only are the numbers not always precise, but to my certain knowledge no historian has attempted to add them all together. Someone probably should, with the caveat that it could only be a low estimate. As Colin Lucas (an historian whose analyses should be taken with a grain of salt, in my view, but who is reliable enough for this kind of statistic) puts it in L’État de la France pendant la Révolution (1988, p. 223),

De grands massacres dans les prisons jalonnent ces mois [de floréal à prairial an III] : le 15 floréal (4 mai), 99 morts à Lyon ; le 21 floréal (10 mai), 60 à Aix-en-Provence ; le 6 prairial (25 mai), 24 à Tarascon ; le 14 prairial (2 juin), 11 à Saint-Étienne, 100 à Marseille et, le 2 messidor (20 juin), de nouveau 23 morts à Marseille. Ils s’accompagnent d’attaques contre les convois de prisonniers, par exemple à Pont-Saint-Esprit ou à Bourg-en-Bresse. Ce ne sont là que les faits les plus spectaculaires émergeant d’un fond sanglant de morts individuelles, de voies de fait, d’arrestations multipliées. Une documentation déficiente ne permet pas de chiffrer les morts. Pour les Bouches-du-Rhône, on a cité près de 850 victimes pendant l’an III et l’an IV : mais l’acception à cette époque d’“assassinat”, qui n’implique pas nécessairement un décès, laisse flotter l’incertitude.

Françoise Brunel (Dictionnaire de la Révolution française, 1989, p. 1025; see also her article “Clore le gouffre de la Terreur”, 1994) cites numbers that seem to be a bit lower, but just as impressionistic:

[…] sur 415 homicides dénombrés de l’an III à l’an V dans les Bouches-du-Rhône, le Vaucluse, le Var et les Basses-Alpes, 66% s’inscrivent en trois mois (floréal-messidor an III). On compte aussi 150 victimes dans le Rhône et la Loire, des dizaines en Haute-Loire, Ardèche, dans le Gard et la Drôme. Meurtres isolés ou sabrages collectifs, ces événements doivent être replacés dans la politique post-thermidorienne.

This is about as close as you get to an estimate on the numbers; the same goes for books on the Thermidorian Reaction, I’m afraid.

Interesting to note, the victims of the repression in Paris are generally regarded as part of a separate phenomenon, and not counted together with the people massacred in the Midi, but we do have more precise figures for the judgments of the military commission put in place to try the participants in the insurrection of Prairial Year III in particular: 36 death sentences, 11 deportations, 7 sentenced to a chain-gang, 34 sentences of imprisonment (not counting the 2500 or so arrested after 4 Prairial Year III and kept in prison without judgment) and 60 acquittals.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today, the month Prairial of the French Republican Calendar starts. You can find the full calendar here.

My scythe only made the hay of the Prairie fall In order to nourish, during the winter, the useful herds; Likewise I will take care of the caressing birds, Which your burning love makes hatch into life.

Revolutionary dates:

1 Prairial Year III: Insurrection of 1 Prairial

31 May - 2 June 1793: Journées (fall of the Gironde)

13 Prairial Year II: Battle of 13 Prairial (known as the Glorious First of June in Anglophone historiography)

20 Prairial Year II: Festival of the Supreme Being

22 Prairial Year II: Law of 22 Prairial

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Committee of Public Safety (F. Brunel)

The trace left in history be the most famous of the Convention's committees is profound and sometimes unexpected: it was, let us remember, the schemes of a rebellious Committee of Public Safety which presided over the instauration of the Fifth French Republic.

One must not be surprised by the late creation of the committee. While the notion of salut public was one of the founding concepts of the Revolution, the Assembly could fear that the ascendancy of such an institution would be too great, and, at the same time, that it would infringe upon the remit of the Provisional Executive Council and that it would tend towards an autonomy contrary to the principle of legislative centrality. Thus, on 1 January 1793, the Girondin deputy Kersaint only proposed the establishment of a Comité de défense générale which was to be composed of deputies chosen among the members of the seven committees (War, Marine, Colonies, Finances, Trade, Diplomatic Committee and Constitution Committee). This new committee at first gathered thrice per week, later, from 21 January onwards, every day, even two times per day, at noon and at seven o'clock in the evening. The defeat of Neerwinden and the beginning of the Vendéan insurrection justified the creation of an ephemeral Commission de salut public on 25 March 1793: the term was therefore finally adopted. On 6 April 1793, the Convention decreed, at the end of a long debate, the creation of a Comité de salut public and immediately proceeded to the election of its members by roll-call. The first nine elected members were Barère, Delmas, Bréard, Cambon, Danton, Jean de Bry (who resigned, being replaced by R. Lindet), Guyton-Morveau, Treilhard and Delacroix (d'Eure-et-Loire). They held two sessions per day (at nine o'clock in the morning and seven o'clock in the evening) in the Pavillon de Flore (renamed Pavillon de l'Egalité). On 30 May 1793, the Convention added five deputies charged with presenting the articles of the constitution, Hérault de Séchelles, Ramel, Saint-Just, Mathieu and Couthon. After the fall of the Gironde, the Committee of Public Safety was reorganised: bureaus were created and the affairs were divided into six sections. Enlarged by successive elections, it counted eighteen members on the eve of the new reorganisation of 10 July 1793. On this day, the Convention decided to re-elect nine members by roll-call: these were, elected in this order, Barère, Jeanbon Saint-André, Gasparin, Couthon, Hérault de Séchelles, Thuriot, Prieur (de la Marne), Saint-Just and Robert Lindet. On 27 July, Robespierre replaced Gasparin, who had resigned, and on 14 August, Carnot and Prieur (de la Côte d'Or) were elected. On 6 September 1793, at last, Billaud-Varenne and Collot d'Herbois made their entrance, whereas Danton and Granet refused their election. After Thuriot, in turn, resigned on 20 September, the Committee of Public Safety was the composed of twelve members, Twelve Who Ruled, to use Robert Palmer's suggestive [...] formula.

What one calls the « great Committee of Public Safety » – composed, in fact, of eleven deputies, as Hérault de Séchelles, sent on mission in Alsace, denounced in Frimaire Year II and executed in Germinal, no longer sat there – has aroused the attention of historians. Relying, sometimes uncritically, on post-Thermidorian sources (particularly the Reports of Le Cointre and of Saladin or the Defences of Barère, Billaud and Collot), historiography has erected the committee as the centrepiece of the « Jacobin dictatorship ». One has often paid particular attention to the growing number of its employees (67 in Frimaire, 418 in Prairial Year II), the sign of an undeniable « bureaucratisation », to its agents (such as Eve Demaillot, Pottofeux or the young Jullien, called Jullien de Paris) who had became an executive power independent of the Convention, and, finally, to its Bureau de police générale, whose activities, from Floréal to Thermidor Year II, had largely overflowed onto the duties of the Committee of General Security. All of this demands to be nuanced. First of all, because the law of 14 Frimaire Year II clearly defined the area of competence of the Committee of Public Safety, which was obliged to report to the Convention every month and was composed of deputies who were elected and personally responsible. The decree of 27 Germinal Year II (16 April 1794), which clarified that the supervision of public servants was confided to the Committee and which led to the creation of this bureau de surveillance administrative et de police générale, hardly modified, in this regard, the Law of 14 Frimaire (2nd section, article 2). As to the « rivalry » between the bureau and the Committee of General Security, Arne Ording has demonstrated that it was necessary to moderate it, at least until Messidor Year II, when a conflict undoubtedly broke out about the commissions populaires which had been created in Floréal.

If the Committee of Year II has aroused publications and polemics, it has also reasonably clouded the history of the post-Thermidorian Committee. It has also been accepted that the decree of 7 Fructidor Year II (24 August 1794) deprived it of its essential prerogative, thereby bringing about the « dislocation » of the Revolutionary Government. Yet, reading article I of title II, which defines the new duties of the Committee of Public Safety, this affirmation does not seem to be totally clear. Even if, indeed, it lost « the supervision of the civil administrations », henceforth entrusted to the Committee of Legislation, it retained functions that were no less important, such as the « direction of foreign relations », the planning of campaigns, the levying and organisation of troops, the supervision of the military agents and, together with the Committee of General Security, the possibility to arrest the civil servants who were within its purview and to send them before the Revolutionary Tribunal. Its twelve members were renewable by a quarter every month (like the members of all committees), but ineligible to the two committees of General Security and of Public Safety for at least a month ; they were appointed by roll-call. The names of the deputies who were elected in Year III seem to highlight the persistent and known importance of the committee ; Merlin (de Douai), Boissy d'Anglas, Sieyès, Reubell or Cambacérès, for example, cannot pass for obscure deputies. On 14 Germinal Year III (3 April 1795), the number of its members was increased to sixteen, and on 21 Floréal (10 May 1795), on a proposal of Cambacérès, the Committee of Public Safety recovered a kind of pre-eminence, being declared the only institution capable of issuing legally binding decrees. From Floréal to Fructidor Year III, it was dominated by the moderates and, particularly, by the Girondins who has been reinstated (eight of them sat there on 15 Prairial: Aubry, Defermon, Henry-Larivière, Rabaut-Pornier, Pontécoulant, Gamon, Blad and Vernier, i.e. half of the committee's members). The last vote, on 15 Vendémiaire Year IV (7 October 1795), was marked by a return of the « Montagnards réacteurs », the election of Chénier, Eschassériaux and Thibaudeau, marking the « anti-royalist » line of the aftermath of the Parisian insurrection.

Thus, until the disbandment of the Convention, the Committee of Public Safety remained one of the essential organs of the Revolutionary Government, and the concern to be elected to it, clearly displayed by the post-Thermidorian leaders, undoubtedly reveals its leading political role.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

#French Revolution#frev#committee of public safety#csp#year ii#translation#robespierre#couthon#barère#saint-just#saint just#collot d'herbois#collot#lindet#prieur de la marne#Prieur de la Côte-d'Or#billaud varenne#billaud-varenne#carnot#saint-andré#saint andré#hérault#hérault de sechelles#francoise brunel

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

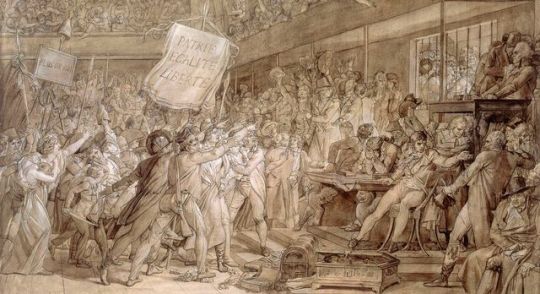

The Insurrection of 1 Prairial Year III (Raymonde Monnier)

The failure of the journées of Germinal had consolidated Thermidorian power. The repression of the insurrection, the arrest of the militants and the disarmament of the terrorists by virtue of the decree of 21 Germinal, weakened the popular movement at a time where scarcity, turning into famine, again mobilised the masses. The insurrection was brewing ; the signal was given, on 30 Floréal, by the pamphlet Insurrection du peuple pour obtenir du Pain et reconquérir ses Droits, undoubtedly written by the ringleaders that were imprisoned at Plessis. Reviving the children of the democratic Revolution, it called for a mass demonstration at the Convention on the next day, with the watchword: Bread and the Constitution of 1793. From 5 in the morning onwards on 1 Prairial, the tocsin rang in the Faubourgs Antoine and Marceau ; groups of women and workers roamed the streets in order to call to arms. The sectionnaires attempted to involve the constituted authorities and headed towards the Convention. The decisive assault took place when the battalions of the Fauborg Antoine arrived ; the crowd invaded the Convention at half past 3 in the afternoon. In the fray, the deputy Féraud was killed and his head was carried around on a pike. While the insurgents engaged in confused agitation, without thinking of attacking the Committees, the latter, not without trouble, organised an armed force with regular troops and the battalions of the eastern sections. The deliberations at the Convention started again around 9 o'clock ; the Montagnard deputies then prompted the Convention to vote on decrees that were favourable towards the insurgents: the liberation of the imprisoned patriots, the appointment of a provisional commission to replace the Committee of General Security. But the armed force of the moderate sections chased the crowd out of the room and the liberated Convention decreed the arrest of fourteen deputies. The trap snapped shut ; the sans-culottes have lost the advantage. They attempted to take revenge on the next day.

Yet, on 2 Prairial, they committed the same error as the day before. The insurrection started again while the sans-culottes formed illegal assemblies in the sections. In the afternoon, the battalions of the Faubourg Antoine again marched on the Convention. It was in extreme peril around 7 o'clock, when the gunners of the Faubourg, aiming their cannons at the Convention, brought about the defection of the gunners from the moderate sections. But the insurgents allowed themselves to be taken to promises and to a faked « fraternisation » of the deputies and returned to their sections when the night came. They had lost their last change. The military reduction of the Faubourg Antoine, prepared on 3 Prairial by the government, which had 20,000 men at its disposal, was carried out in the evening of 4 Prairial.

The repression was organised immediately. A military commission, created on 4 Prairial, pronounced 36 death sentences, 11 deportations, 7 peines de fers, 34 detentions and 60 acquittals. Eighteen of the 23 gendarmes that had defected to the insurrection were condemned to death, as well as the « assassins » of Féraud and 5 leaders of the insurrections, among them the captain of the gunners of Popincourt, Delorme. The six deputies that were condemned to death, Bourbotte, Duquesnoy, Duroy, Goujon, Romme and Soubrany, the « martyrs of Prairial », attempted suicide. The repression of the sections was much more extensive ; arrests and disarmaments affected more than 2,500 militants, Jacobins and sans-culottes of Year II, even if they had not been involved in the insurrection. The repression varied according to the sections (in the report from 1 to 7 Prairial), and generally was based on the violence of the struggles of Year II and Year III, as well as on the capacity of resistance of the militant sans-culottes ; it principally affected the former revolutionary commissioners and the Jacobin leaders. The National Guard was reorganised on 28 Prairial, as the workers and citizens that were « peu fortuné » were removed from it. The popular movement was knocked down and disarmed. The insurrection of Prairial, probably organised from the prison of Plessis, had, once it had started, lacked leaders. Its failure allowed the Thermidorians to eliminate the last representatives of the Montagne and the popular movement. Isolated, facing a bourgeoisie that was virtually united against it, the popular movement ceased to be a political force. The Thermidorian reaction had reached its goal.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

Image source: L'insurrection du 1er Prairial An 3 ( 20 mai 1795 )

#french revolution#frev#prairial#year iii#post-thermidor#post#translation#romme#montagne#montagnards#dhprairial#raymonde monnier

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Thermidorian Reaction (Françoise Brunel)

It certainly cannot be a matter of outlining the account of the fifteen months which passed between 9 Thermidor Year II and the disbandment of the Convention (4 Brumaire Year IV / 26 October 1795) here, but rather of attempting a brief clarification on a period that has been abandoned by historiography for a long time and has recently been revisited by new researches.

One has emphasised how the traditional division of the Convention into three periods, « Girondin », « Montagnard » and « Thermidorian », was more opacifying than explanatory. The envisaged sequence cannot, in fact, be reduced to a « reaction » (in the classical as much as in the modern sense of the term), nor can it be defined by the designation « Thermidorian » which, by assigning a largely artificial starting point to it, erases its ruptures and continuties (let us recall that neither the abolition of feudality and of colonial slavery, nor republican symbolism were challenged at that point). Thus, when Albert Mathiez wrote « réaction, cela veut dire retour en arrière, recul », he took into his account the speeches of the « last Montagnards », of the militant sans-culottes and still of Babeuf who, starting from Nivôse - Pluviôse Year III, concentrated their criticisms on the abandonment of the democratic measures that had been adopted in Year II (the Maximum was repealed on 4 Nivôse Year III / 24 December 1794), being indignant over both the « persecutions » suffered by the « outspoken patriots » and over the increasing misery of the popular masses, particularly in the cities. But thereby, Mathiez reduced the specifics of this period and its innovations to nothing. Let us not follow the analysis of Georges Lefebvre, either, who concluded that it was a matter of « returning to the Revolution of 1789, which had had the purpose of assuring the political and social preeminence of the bourgeoisie ».

It is right, no doubt, to take seriously the watchword « Neither 1791, nor 1793 » (and its variants à l'antique, « Neither the monarchy of Tarquin, nor the dictatorship of Caesar ») which gradually imposed itself, because it summarises the post-Thermidorian creation and, along with it, the Directory's attempt of stabilisation (at least in its beginnings). Numerous facts demonstrate that Year III was not supposed to be a « return to 1789 ». It was, firstly, this « instrumentalisation » of the revolutionary government which prepared the empowerment of the new post-revolutionary State, the emergence of a « political class » (this is also one of the meanings of the Two-Thirds Decree) and the famous caesura between « civil society » and State. Secondly, the Convention introduced the « parliamentary coup d'état », of which our history offers many examples, from 18 Brumaire to 1958, by writing (in spite of the referendum of 1793) a new Constitution, which was equally distant from the two « models » of 1791 and 1793, and which, most importantly, abandoned the liberating universalism of 1789 by erasing every reference to the « natural and imprescriptible rights of man » from its Declaration of the Rights and Duties. This is why 1795 marks something else than a « reaction » : Year III signs the end of the Revolution and, in this regard, even represented its negation. If, however, the word « reaction » has prevailed, it is because a brutally reactionary phase was inscribed into the heart of the post-Thermidorian moment, between the illusions unitaires of the beginning and the establishment of the new republican order which brought it to a close.

This leads us to schematically indicate the chronological rhythms of the period. The first sequence, from Fructidor Year II to Frimaire Year III, was characterised by a double process of the investment of the revolutionary government, and of the preparation of public opinion. The liberation of suspects and the indefinite liberty granted to the press emerged at that point, as well as purges, punctual at first, then massive, which struck the « accomplices of Robespierre », both in Paris and in the provinces : the new representatives en mission, « Montagnards réacteurs » or Conventionnels of the Plain, played an essential role then. In order to perfect this offensive, two conditions were indispensable :shattering the network of popular societies and making an example of a « great culprit » who was supposed to incarnate the « terrorist » policy (a neologism that was quickly in fashion). On 25 Vendémiaire Year III (16 October 1794), a decree forbade collective petitions, affiliations and internal correspondences to the popular societies. The end of the Jacobin Club, this « den of brigands and cannibals », constituted the last step : after incidents (encouraged by certain deputies, such as Rovère or Fréron) broke out between the « muscadins » and Jacobins, the Society of the Friends of Liberty and Equality was officially closed on 22 Brumaire Year III (12 November 1794). In Frimaire Year III, the process of Carrier and its consequence, as well as the recall of the Girondins who had protested against 2 June 1793, fall within this logic, allowing the deputy Clauzel to resume, on 30 Frimaire Year III, the denunciation of the former members of the Committees of Public Safety and General Security, an action which had been judged as « calumnious » in Fructidor Year II : the time of illusions was over.

From Nivôse to Prairial Year III, the violent mise au pas of the democratic movement unfolded. We will not revisit it, because its primary aspects have been treated elsewhere. It is, against the backdrop of the social struggles that were exacerbated by the supplies crisis and the inflationist explosion, « the defeat of the sans-culottes », the purge of the Convention through arrest, deportation or death sentence of 74 out of the 100 « last Montagnards », it is also the « White Terror » in the departments and, above all, the disarmament of the « Terrorists » and the fight against the « buveurs de sang ». This brutal deconstruction of the system of Year II renders the parliamentary coup d'état possible, but also constituted what immediately weakened the future power. Finally, the last sequence, from Messidor Year III to Brumaire Year IV, illustrates the difficulties of peacefully instituting the republican order. While the émigrés were crushed in Quiberon (Thermidor Year III), the new Constitution, adopted on 5 Fructidor Year III (22 August 1795) after two months of debates which were sometimes stormy, claimed to be the one of « the middle class », of the « honnêtes gens ». But the « royalists » were indignant over the Two-Thirds Decree, which harmed the liberty of a suffrage that was nonetheless censitary, whereas the « anarchists » denounced a regime that gave the « rich » more than their share.

The Directory would never address these two perils, except through politico-policial coups de force (J.-R. Suratteau). War of conquest, resumed in Year III with the invasion of the Dutch Republic, paved the way for an authoritarian stabilisation, the one of order by means of the sabre.

Further reading

A. MATHIEZ, La réaction thermidorienne, 1929.

G. LEFEBVRE, Les Thermidoriens, 1937.

F. BRUNEL, « Sur l’historiographie de la réaction thermidorienne... », AHRF, 1979, p. 455-474.

M, OZOUF, « Thermidor ou le travail de l’oubli », L’école de la France..., 1984 ; Dictionnaire des usages socio-politiques de la langue française (1770-1815), fascicule 1, Klincksieck, pub. INeLF, 1985 (art. « Buveurs de sang », « Crête, Crétois » and « Honnetês gens »).

F. BRUNEL, « Aux origines d’un parti de l’ordre : les propositions de Constitution de l’an III », Mouvements populaires et conscience sociale, pub. by J. Nicolas, 1985.

B. BACZKO, « Robespierre-roi ou comment sortir de la Terreur », Le Débat, n° 39, p. 104-122.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

#French Revolution#frev#robespierre#thermidor#post-thermidor#post#francoise brunel#translation#thermidorian reaction

23 notes

·

View notes